A key policy of the Albanese government is the Capacity Investment Scheme which will see the taxpayer openly subsidise wind and solar projects to be constructed and operated in Australia’s National Electricity Market.

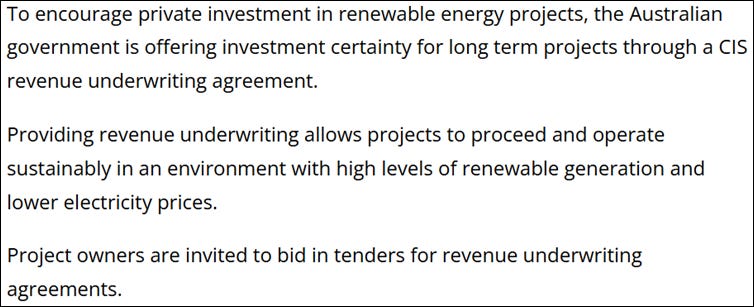

There is some debate throughout energy circles about how the CIS functions to guarantee revenue for wind and solar projects. There is little doubt the scheme offers a revenue guarantee:

Source: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/energy/renewable/capacity-investment-scheme#transcript

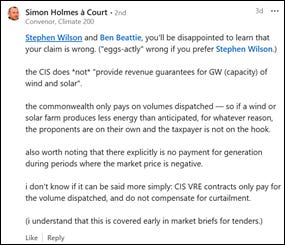

Some have suggested that the projects are only paid according to their final output:

Source: Simon Holmes a Court via LinkedIn

Is Simon correct about the nature of the scheme? Here I’ll show how he’s missed why the CIS will cost taxpayers billions.

In order to fully understand the payment mechanism we should turn to the legally binding tender documents, for which the government has made available the pro-forma Capacity Investment Scheme Agreement (CISA):

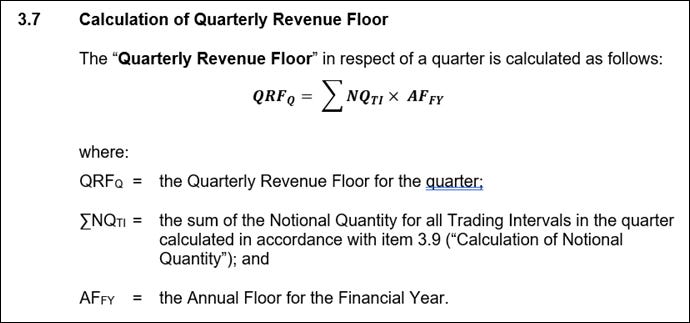

The CIS imposes a financial collar on wind and solar projects – earnings above the revenue ceiling receive a 50% penalty while earnings below the revenue floor attract a 90% top-up. The agreement is reconciled quarterly. Pretty simple on the face of it.

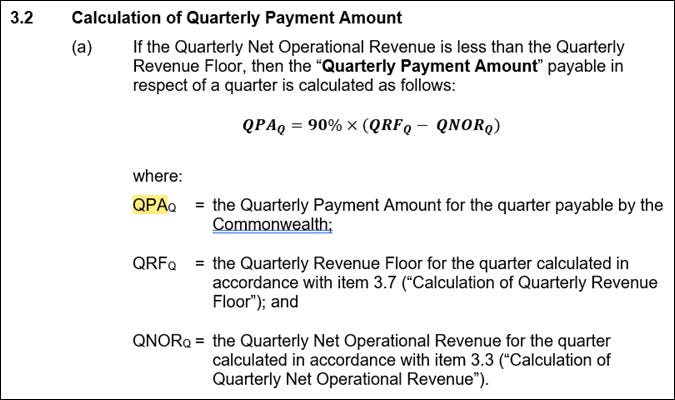

Section 3.2 of the CISA describes the payment calculations for earnings outside the floor and ceiling thresholds. Here we are considering the revenue top-up component of the CISA because that will be the cost to taxpayers.

In simple terms, the quarterly top-up payment is 90% of the difference between the quarterly revenue floor and the projects actual revenue, so if the project makes some revenue, but less than the agreed floor revenue, the top-up kicks in.

Here’s where the work starts for us, to understand exactly what makes up the agreed quarterly revenue floor, and actual revenue.

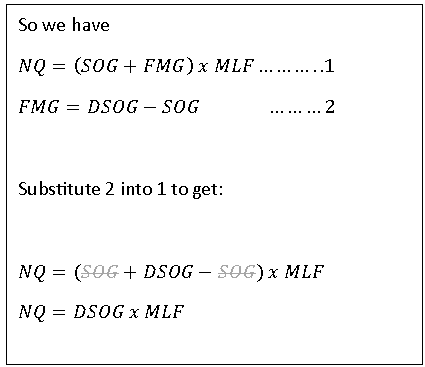

Quarterly revenue floor is notional quantity multiplied by the annual floor value. The annual floor is defined by the project in the contract as a $/MWh figure. So far so good, but what is notional quantity?

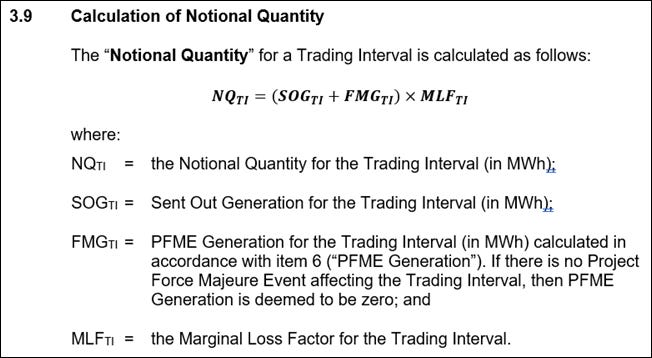

It turns out the notional quantity represents the projects output in MWh. This makes sense, because the quarterly revenue top-up then becomes $/MWh x MWh, which leaves $. Notional quantity is used in a couple of places in the CISA calculations, but here we are focusing on the impact to taxpayers.

The calculation for notional quantity includes a couple of variables. MLF is marginal loss factor and applies to all projects regardless of technology and is dependent on the physical location relative to the transmission network, so this doesn’t matter much to us.

The two variables inside the brackets matter the most – these are sent out generation (SOG) and force majeure generation (FMG). Here is our first confirmation on how the CIS props up otherwise uneconomic wind and solar projects. What is force majeure in the CISA and why does it increase the electrical output of the project?

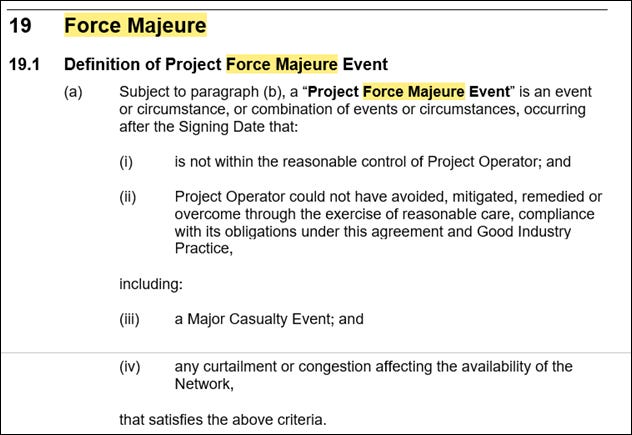

Like most legal and binding documents, the CISA includes detailed definitions of terms used within it.

From the definition please note item (iv) any curtailment or congestion affecting the availability of the Network. The CISA specifically states that network curtailment or congestion is a force majeure event for the purposes of the contract.

Readers might recall AEMO’s most recent publication that discussed current and future curtailment or congestion…

The force majeure definition goes on to exclude a few conditions, most notably the weather. This is good, because taxpayers don’t want to pay a top-up when the weather is not favourable.

But back to the curtailment or congestion part, and the CISA fails to further define congestion or curtailment. The calculation for generation output refers to Item 6 which introduces another variable called deemed sent out generation (DSOG), and this is the final nail in the coffin for those who believe the capacity investment scheme only tops-up projects based on sent out MWh.

It turns out that deemed generation is a calculated number using some method yet to be determined, and the project is paid based on what it would have generated if the curtailment or congestion had not occurred.

In terms of top-up payments, it appears very clear that CIS projects are financially well protected – not from weather – but from curtailment. When you consider the amount of curtailment or congestion occurring now, and then the CIS is aiming to add a further 23 GW to the existing 27 GW fleet, the scope for network curtailment or congestion is massive.

Even RenewEcomedy’s David Leitch agrees with that! https://wattclarity.com.au/articles/2025/02/a-look-at-curtailment-through-the-gsd2024/

So it makes perfect sense the CIS was designed with this in mind, hence the very clear direction in the CIS agreement to allow projects to claim payment for MWh lost to curtailment or congestion.

Let me guess, no one has modelled it?

Capacity investment, solar farm investment, wind farm investment.....

The simple fact is that the various schemes to encourage VRE investment over some 15 years have failed to reach levels anywhere near what's needed to run exclusively VRE based generation adequate to replace the existing, within our lifetimes. It's not the way to get a reliable power supply running. How long will you Neroes keep fiddling?